Some have stated that the current tone of public discourse currently in the United States is much like it was shortly before shots were first fired in the U.S. Civil War in 1861. Of course, nobody is alive today that experienced life in 1861 and can vouch for such a call. But a quick study of pre-Civil War politics and the dynamics of the civic tone of those times would indeed reveal a profound division among the masses. Good will, compromise and negotiation were out. Deep divisions of opinion rooted in States’ rights were underpinned by the issue of slavery. Everyone had their own opinion, and nobody was going to give an inch. Folks divided into tribes, either for or against the issue of states’ rights and slavery. Of course, everyone believed their position was rooted in tradition, correctness, and moral high ground. And on top of that was the expectation of providence and economic prosperity. Does that sound familiar? Some argue we see the same parallels today.

I posit we can better understand today’s political divisions and possible solutions if we examine the U.S. Civil War and the horrors experienced by all participants in that ugly time in U.S. history. Many of those participants we claim as not-too-distant ancestors. At the very least, we will see first-hand what can and likely will happen on our own home front if we don’t figure out reasonable solutions to what divides us today – and fast! And maybe a good place to start would be sitting down together at the same table and identifying common values we can all agree upon. And then move from there to a position of trust in dealing with the issues we cannot agree on.

Years ago, as a student studying the art of conflict resolution during graduate studies, I spent countless hours mediating conflicts. I discovered that one of the most difficult steps in successful mediation involves getting combatants to sit at the same table and find some level of commonality. In that space, a level of decorum will hopefully be established where an environment of mutual trust can take root, and ensuing compromise can take place. But when a conflict reaches levels of intractability, hope in compromise and ensuing peace is typically lost. At that point, war often becomes imminent. Some might argue we are near that point today, right here in the United States.

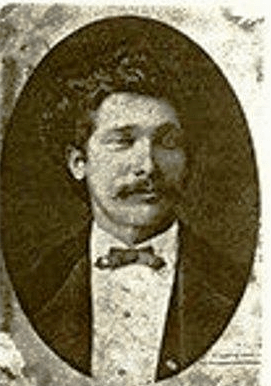

In this discussion of the U.S. Civil War, I will focus on an interesting drama that took place in Schuyler County, Missouri near the start of the war. I think there are some things we can all learn from the experiences of my great, great, great grandfather, William Henry “Hand” Lile. He was nicknamed “Hand” because when he was ten years old, he lost his left hand in a farming accident. Like any tough kid would do, he learned to use his right hand for everything to compensate for being one-handed. Having only one hand, he became notorious around town for his shooting skills and doing farm work and everything else expected of a man during those times.

William Henry Lile came from hard-living, tough, farmers and laborers. His dad, John, was a brick mason by trade and owned land for farming. Land was a big deal to the family. The Liles migrated to America from Western Europe due to land issues. Early records indicate the Lile family came from a long line of European brick masons and landowners. At some point, the oldest son inherited all the family property, so Henry’s people migrated to America looking for land and prosperity, just like so many others. They settled in what is now Virginia in the mid-1600s. It should be noted that the family name was originally “de Lyle” but was changed shortly after arriving in America. Henry’s grandfather changed the spelling to “Lile” for reasons unknown.

Henry’s grandfather, who had the same name, William Henry, and his family left Virginia and migrated west through Kentucky. That grandfather was killed in a skirmish with Indians around the year 1800. Grandpa Lile’s father, John, moved the family on to Missouri and were some of the first settlers who moved into that territory after the Louisiana Purchase. Northern Missouri was free and beautiful.

Grandpa Lile bought a 121-acre farm in 1857 near Lancaster, the Schuyler County seat. The county was formally organized in 1845 and named in honor of General Philip Schuyler of the Revolutionary Army. When Grandpa bought his farm, he was 32 years-old with a wife (Angeline) and seven kids. My Great, Great Grandmother, Anna, would come along in 1859 – two years later. It should be noted that, according to the 1850 and 1860 census information, none of my Lile ancestors owned slaves.

So that sets the foundation describing the Lile family and their heritage. Interestingly, the name “Lile” or Lyle has been passed down through my family generations in honor of this great family. My Great, Great Grandmother, Anna Lile, mentioned previously, married into the Hicks family in 1878. My grandfather Harry and younger brother Robert share the name “Lyle” as a middle name in honor of those great Lile ancestors.

So, to continue Grandpa Lile’s story and the lead-up to his involvement in the Civil War, let’s establish some important information regarding Missouri and its involvement in the Union at that time.

Controversy over whether Missouri should be admitted into the Union as a slave state resulted in the Missouri Compromise of 1821, which specified that territory acquired in the Louisiana Purchase north of latitude 36° 30′, which described most of Missouri’s southern border, would, except for Missouri, be organized as free states, and territory south of that line would be reserved for organization as slave states. So, Missouri became a slave state when it was granted statehood in August 1821. As part of the compromise, Maine was admitted as a free state the same month.

When the Civil War started, one must keep in mind that in the state of Missouri, there were a mixed bag of sympathizers for both the Confederate and Union causes – that, despite the fact it was a slave state. During the war, Missouri supported the war effort on both the Union and Confederate sides. As a result, acute divisions played out among acquaintances, friends, and families in Missouri communities. Fighting and bickering took place in those tight communities that otherwise were full of friendly people who likely belonged to the same religious organizations and community groups. The bickering often centered around the rights people should have in their own pursuits of happiness guaranteed by the Bill of Rights.

Grandpa Lile was caught up in the political furor of the day. However, his brother Dan was reportedly even more “rabid” about state’s rights and the inherent rights of farmers and landowners to be free from government intrusion. It is reported through family records that his brother Dan riled up Grandpa Lile and together in 1861, they left their wives, kids, and farms and joined the war on the side of the Confederacy. Like so many others, they likely figured the war would end soon, their point would be made, and everyone would return home and the fight would be over.

That didn’t happen. In fact, that same year, at different times, both Dan and Grandpa Lile were captured by Union forces and became prisoners of war. Grandpa Lile, as far as my research could uncover, was wounded at the time he was taken prisoner. He was first held at a prison in St. Louis. Then he was moved, via the Mississippi River, to Alton Prison in Illinois, located near the banks of the river. And that’s where things took a turn for the worse.

In 1833, the Illinois State Prison in Alton was built as the first state penitentiary. In 1857, the prison was closed and replaced by a new state prison in Joliet. At that time, the Alton prison had a total of two-hundred-fifty-six cells. In early 1862, the U.S. government reopened the Alton prison to house Confederate prisoners of war. The first prisoners arrived on February 9 of that year.

The prison was originally built to house 900 inmates. However, during the Civil War, the prison’s average population was about 1,200. In January 1865 – the year the prison was closed for good, the population peaked at 1,900. When Grandpa Lile arrived, it is estimated the prison population was around 1100.

Prison life at Alton was deplorable and conditions led to sickness and disease. Pneumonia, smallpox, rubella, and dysentery were all feared killers among the prisoners. Grandpa Lile realized his situation was dire.

According to a local librarian who reviewed early war records at the Schuyler County library in Lancaster, Missouri, “Both [Dan and Grandpa William Henry Lile] took the Oath of Allegiance to the North to get out of prison. Both went back to Missouri where William kept the oath. This is documented by a file that [the librarian] copied at the National Archives.”

Sadly, Grandpa Lile died on September 9, 1862, only a few weeks after returning home to his family and farm. He was 37 years old. The official death notice indicated he died from wounds received in battle. He was buried at a family plot in the Helton Cemetery in Macon County, a relative short distance from his home in Lancaster.

Grandpa William Henry Lile died too soon. And he left a large family – his wife and young kids to fare for themselves during a tough time. Like all stories of this nature, I have a habit of marking the ‘take-aways’ I gathered. What did I learn? Of course, regarding this particular story, I keep in mind that in wartime, emotions and fear influence decisions. In retrospect, perhaps that’s a time when we should be most astute in exercising caution and good judgement. Here are a few of my own thoughts.

- Make important life choices that coincide with personal guiding principles.

- Do not allow others to persuade us to do things that conflict with our personal guiding principles.

- When making choices that involve moral/social correctness and ethics on one side and potential economic prosperity on the other, choose moral correctness and ethics – always.

- When it is realized a wrong choice has been made, it’s okay to change, take corrective action, and realign personal values and principles.

Those are my takeaways. If you see any others, please feel free to note them in the comments. Thanks for reading!

Leave a comment