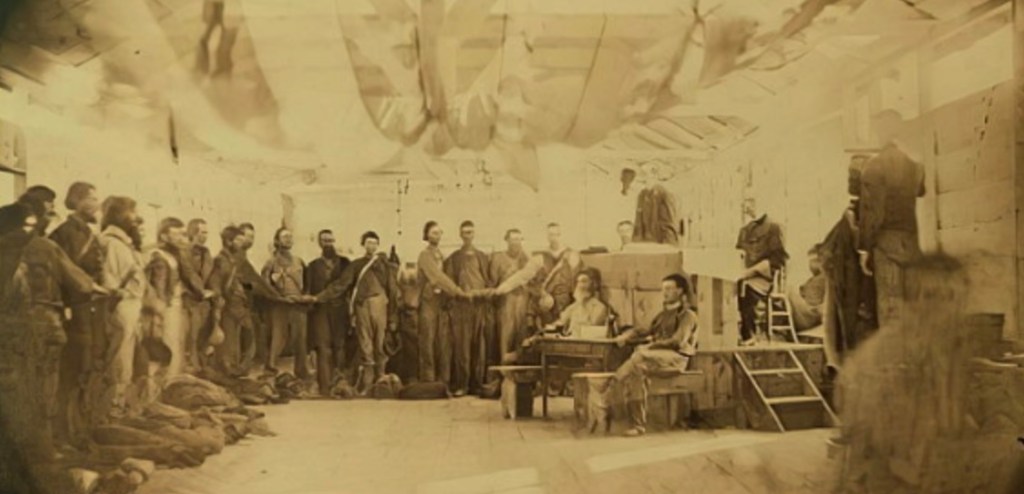

In early 1862, both my GGG grandfather, William Henry Lile, and his brother Daniel, who were Confederate soldiers, were both captured and sent to Alton Military Prison in Illinois, located along the banks of the Mississippi River. They both took the Oath of Allegiance to get out of prison. So, what was the Oath of Allegiance and why was it important?

Beginning near the start of the Civil War, an Oath of Allegiance was offered to Confederate military prisoners as a type of parole. Those who officially took the oath were set free and allowed to return to their homes and families. After being set free, if at any point the parolee broke the oath and was caught, then he would likely be executed. Breaking the oath usually involved the parolee taking up arms against the United States government or its officers – meaning the government of the north.

Of course, there was some trepidation among the Confederate prisoners in taking such an oath. In their minds, they were not United States citizens and owed no loyalty whatsoever to the U.S. Constitution or the United States government. They were loyal to the Confederate States of America. However, if it meant getting out of prison and free from the horrible conditions there, many chose the Oath of Allegiance.

I found some old news articles from Alton, Illinois – the location of the military prison where my ancestors were kept. Apparently, some of the town folks were concerned because Confederate prisoners were being set free after taking the oath and were walking the streets of town with no money and no food. The tone of the article was split between charitable concerns and fear the freed prisoners might be dangerous.

The wording of the Oath of Allegiance that my ancestors took is as follows: “I […] do solemnly swear that I will support, protect, and defend the Constitution and Government of the United States against all enemies, whether domestic or foreign; that I will bear true faith, allegiance, and loyalty to the same, any ordinance, resolution, or laws of any State, Convention, or Legislature to the contrary notwithstanding; and further, that I will faithfully perform all the duties which may be required of me by the laws of the United States; and I take this oath freely and voluntarily, without any mental reservation or evasion whatsoever.”

Of course, there were some who deliberately broke their oath or were accused of breaking their oath. The penalty for doing so was severe. The following account relates the story of what became known as the Macon Massacre, which occurred in the state of Missouri. The first account is a layman’s account of what happened. Following that, an official report, likely from a news source, is given.

In September 1862 twelve men were brought to the Macon City prison, all of whom had taken the oath but had been caught fighting against the Union again. One of the prisoners escaped and the other eleven were taken to the southwest lookout point and by order of General Lewis Merrill were to be executed. Sixty-six soldiers were assigned – six per man – to shoot the rebels. On Merrill’s order to “Fire,” ten were killed but one survived. Merrill assigned six men again and said, “Finish the deed,” and he rode off on his horse. Meanwhile, a woman had thrown her body over the injured man on the ground. All six soldiers fired in the air. The injured man was quickly carried away. It is not known if he lived or died. The execution became known as the Macon Massacre.

The Massacre Rock marks the historical site where the Macon Massacre occurred in September 1862 during the Civil War. It is located southwest of town in what is now Woodlawn Cemetery. In September 1862, ten Confederate soldiers were sentenced to death in Macon City. According to Official records, “… having once been pardoned for the crime of taking up arms against their government and having taken a solemn oath not again to take up arms against the United States, have been taken in arms, in violation of said oath and their solemn parole, and are therefore ordered to be shot to death on Friday, the 26th of September, between the hours of 10 o’clock a. m. and 3 o’clock p.m.”

The Confederate soldiers were executed by a firing squad from the 23rd Missouri infantry. All town folk who were suspected of being sympathetic to the Southern cause were rounded up and forced to watch the bloody display. The Massacre occurred in what is now Woodlawn Cemetery, in the southwest portion of Macon off Coates Street.

As I mentioned in a previous essay, Missouri was split between Union and Confederacy sympathizers. The Confederacy claimed Missouri as a state, since it was a slave state, but Missouri also offered considerable support in money and troops to the Union cause. The above account of the Macon Massacre and ensuing horror illustrates that point — the civic strife that ensues within a state when stark political divisions are present .

Discussion in the online Kansas City Public Library was cogent to this discussion. For those interested, please read, “Shadow War: Federal Military Authority and Loyalty Oaths in Civil War Missouri.” This essay highlights the difficulties ordinary citizens encountered in the face of civil conflict.

According to the essay, “The American Civil War, especially in border slave states like Missouri, prompted hardened, albeit sometimes erratic, definitions of loyalty and disloyalty from a population with a wide array of political stances. In 1861 and 1862, [citizens] witnessed the development of a dominion system – an integrated, if imperfectly implemented, knot of counterinsurgency measures conducted mostly by low-level, often volunteer post commanders and assisted by civilian informants. They included:

- Military districting and garrisons;

- Oaths and lists of civilians categorized as “loyal” and “disloyal;”

- Civilian assessments, or levies;

- Martial law, or the suspension of civil authority in favor of military rule.

In this environment, the article states that, “formalized oaths of allegiance became the most ubiquitous symbols of federal authority. The widespread assumption that disloyal majorities of secessionists and neutralists were cowing loyalists in the border states made oaths virtual tools of the occupying troops.”

The essay pointed out, “Many citizens who took the oath did so duplicitously. One woman spat that ‘everyone has been required to take the oath—they are then called Loyal—What a mockery.’ Others refused entirely.”

But was the Oath of Allegiance accomplishing its intent in identifying those who were, indeed, loyal to the constitution and United States government? As the essay stated, “Local residents who took the oath disingenuously believed doing so kept their true loyalties hidden. A resident wrote that some of the residents around him “say that they did not mind taking the oath as they did not consider it binding on them, in fact they would rather take the oath than not as it gives them protection and they can get passes to go where they please.”

“Oaths visibly divided local communities. Civilians who took the oath or posted bond, or both, often found themselves exposed. Visitors known to be disloyal often attracted the attention of armed federals. Reprisals often followed, resulting in societal divisions that in some cases worked to the government’s advantage. Unionists, government troops, and the home guard used the oath against neutralists, Southern sympathizers, and secessionists who refused to take it. Yet disloyal residents often chastised those neighbors who did take it, whether feigned or not, as cowards or disloyal to the Southern Cause.”

One senses from this reading that the civil strife evident in Missouri at this time was like a powder keg ready to blow, and indeed it did, in the form of guerrilla warfare and bushwhacking . The activities defining Missouri and other border states described here offers a clear understanding why it took decades to return to some semblance of civility in these regions, post-Civil War.

The takeaways from this story confirm the horrors of war. Some suggest that right now those same social and political divisions are, on some level, present once again. The question we should all be asking ourselves is: Do we have the collective wisdom and fortitude to avoid another civil conflict dividing communities, families, and friends? We shall see.

Leave a comment