I grew up in Central Idaho where much of my summer time was spent exploring old Ghost Towns. Within a short distance of my hometown, Salmon, Idaho, there are a number of these deserted places. Perhaps you’ve heard of some of them or even visited a few. Names like Leesburg, Forney, and Yellow Jacket might come to mind.

I’m intrigued by these deserted places where empty houses and businesses are rotting in place, and where once busy communities thrived, now deafening silence is all there is to hear. One of my favorite pastimes is examining the history of these ghost towns through the narratives of people who actually lived there.

Yellow Jacket and Forney were places spoken of in Harry Hicks’ life history. Harry is my grandfather, and he left behind a detailed account of his life. He and his family moved to those places in around 1923. They traveled by a horse-drawn wagon from their homestead in Pahsimeroi, Idaho to Forney, then on to Yellow Jacket.

In his own words, Harry recorded this event, which occurred when he was around nine years old.

“Dad and all the family, four of us (mom, my sister Mildred, dad, and me) moved to Yellow Jacket. Dad was hired to work there with his team of horses. The first night I believe we topped the Morgan Creek divide. Mother and dad rode in the covered wagon. Mildred and I ran along the road behind the wagon. We camped the first night just above the old Kingsbury ranch on what was Big Creek, now Panther Creek.

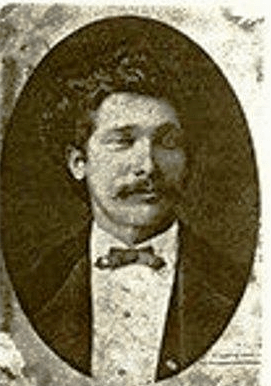

We were to pull out and get into the old stage station on Panther Creek in Forney. The stage station was run by a typical French pioneer named Milt Merritt who wore a big moss horn mustache and spoke in broken French language.

Mother cooked for the freighters that stopped in Forney. They were pilgrims, salesmen, miners, and such. I would meet every freight string of wagons as they came in, and I got to know them all.

There was Hilliard Griebber who was from Tennessee and only drove mules. I’ve seen him drive an eight- or ten-mule hitch with his jockey box full of rocks. He couldn’t reach the leaders with his whip, so he would cuss and throw rocks at them.

There was Ferrell Terry, a gentle sort, but all man, who had a glint of humor always in his eyes. He was the best and quietest of drivers. I worked for him in the CCC Camp much later – a pleasant man, always ready to compliment a fellow with his humor.

I remember Charlie Mitchell, the stage driver. I went to school in Salmon with his boy, young Charlie.

Curt Roberts was another ring-tailed rootin-tootin mean son-of-a-gun from Tenessee, along with Rufus Isley.”

Harry’s family lived in Forney for some time, then moved on to Yellow Jacket. Here is his written recollection of that trip.

“The road as I remember it went up the same side creek where Forney was located, not the canyon where the O’Conner ranch is now. I remember the sounds the horses made as they pulled the two wagons with our stuff and junk. The creak of the leather and the jingle of the chains and the smells of the horses and the plump, plump of those huge hooves as they set down on anything. I could hardly keep my head on my shoulders as the wagon kept rocking around, as this part of the road was creek bottom.

Along in the evening we came to the town of Yellow Jacket that had its beginning through Mr. Steen. Much later, my wife and I was to get to know the son of Mr. Steen – a man in his forties – Heber Steen. What a thrill it was to see the town itself, such a hurry and scurry of building. There was a carnival-like attitude in everyone.

I crossed the Yellow Jacket Creek and climbed up the road about 100 feet to Johnny Dryer’s store to look over his assortment of candy. And if I had enough money, I wanted to try out that new stuff they called soda pop.

Each worker in Yellow Jacket could be identified by his clothes. The regular workers wore overalls, logger boots, and jackets. The company men wore tight-legged pants and tight-laced boots.

As dad pulled our team into the wagon yard, the big team shook their harnesses and gave a big sigh. Everyone gathered around our outfit to see such a big team. They began to carry on a familiar conversation with father about the big team that came up from Camas Prairie several years ago. They had seen them in Challis at the pulling contest. “The very same team, 2200 pounds apiece, you say!” Sure big alright – and such big feet!” And the talk went on. I was so proud as dad led the gentle giants across the creek and they pawed out a hole to drink of the clear creek water.

The next day, we ate a hearty breakfast made by the best cook I have ever known – Charlie Dodge, an old timer from Alaska who was to become a lifelong friend, even though much older than me. He was to be the old Yellow Jacket Hotel cook long after.

The time we spent over at Yellow Jacket was to be an epic time in my life when I was to learn a good many things about the adult race.”

The decade or so before Harry Hicks’ family moved to Yellow Jacket, the mining operations were idle. Then in around 1923, the operations were leased by the New York-Idaho Exploration Company. The company cleaned out old tunnels, built a new boarding and bunk house, and constructed roads. The road building is what Harry’s dad, Victor, got involved in with his team of big horses.

One can still drive from Forney to Yellow Jacket on the same route that Harry described one hundred years ago. Adventurers who plan to embark on the trip, however, will want a decent SUV or side-by-side!

Leave a comment