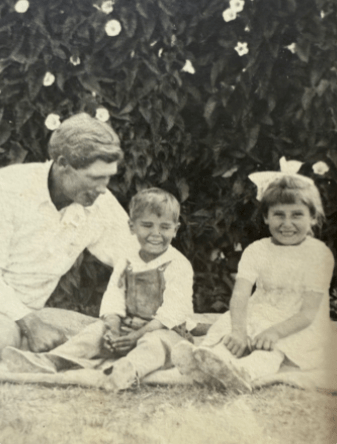

This account of the Hicks family trip to King Hill (Camas Prairie, Idaho) in 1923 was recorded in Harry Hicks’ life history in 1977. A newspaper account was reported in The Idaho Recorder on August 31, 1923 (included on this website).

About that time dad got a Model T Ford truck. It had a worm drive with a Pascal gear. Does anyone know what that is? It meant it would go up the steepest of hills with hard rubber tires on the rear. It had bus seats running along both sides of the rear and a roof over the back. About this time, we took a trip down to Camas Prairie to see all the Hicks family we could. We took several little 15-gallon barrels and went up to Red Fish Lake and, as dad had put in one summer there, he knew how to catch the red fish, not the red suckers you find them catching today.

Well, we caught two or three barrels full in about two hours. We carried them to camp and mother packed them in salt while dad gutted them. We packed everything up and prepared to leave when a man dressed like the engineers at Yellow Jacket used to dress came along and said he was a game warden, and he explained his duties and about this game situation. But none of us had heard anything like that. Dad told him that stuff just wouldn’t work, and they had the wrong idea that there was going to be a lot of men shot and hid out in the bush.

Nevertheless, he told Dad not to be fishing. Dad said he would not until he found out for himself. So, as we drove down, we saw other campers with wagons and teams. Dad told them what that fellow had said, and they started to leave too. They all said they always came up to that lake and got barrels of salted-down fish for winter, and they had their wagons filled with barrels. Sacks of salt. One lady began to cry and cussed the government.

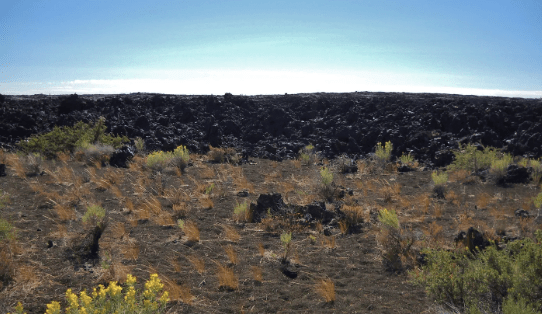

We went back on over to Arco and picked up Mrs. Horne, the mother to Uncle Ralph Silvers. She was to go along with us down to Camas Prairie. Grandad Robert L. Hicks was the 3rd settler on Camas Prairie. When you went anywhere in an old Model T Ford, you were to be always prepared for a long ride. We took a lot of bedding, lanterns, a tent, food, plus 3 or 4 barrels of red fish to treat the folks where we would stay. Us young ones was to ride in the back of the truck along with Mrs. Horne and all the provisions. We got two or three dozen oranges to eat, and the old lady made us save them to eat while we were to go across the lava desert.

We didn’t get up to the mountain pass the first day because of the long pull up to the foothills, which burned out the clutch – low gear. We pulled off beside the road and camped, and dad put a new lining on the clutch. He also had to do this one more time on the trip, but this time he had no lining material, so he had to use his belt to make a lining. Also, the clutch would get so hot dad used to turn around and using the middle pedal, which was reverse, back it up the hill for a while to let the clutch cool off.

Does anyone remember the old Model T and how you had to drive it? How they’re the three coils was hung setting in the box on the dashboard and how they clickety, clickety clack as the electric current went through them, so it would spark the car to run on the Magneto? The later models could be equipped with a battery to make them start easier. I was to be the only one to drive a Model T to high school and had a six or seven foot truck bed. Alvin and Scott Butterfield and I were to take it on an extended week over to Myers Cove on Camas Creek salmon fishing about the summer I finished the 8th grade. Each coil was about the size of a brick, and there were three. If the weather even got damp, they had to be dried out in the oven before they would work.

We left the Lava Rock desert about halfway and climbed up on the big plateau to Fairfield on the Camas Prairie. We camped near a ranch where an old lady had a talking parrot. We stood and listened to him singing old Black Joe over and over. Our astonishment seemed to tickle the old lady, for she cackled as much as the parrot. The next day, we were set upon by the worst rainstorm of my recollection. I remember it so well because we raced our old Ford for a big frame barn we saw in the distance. We had to get that car out of the rain because we all knew it would quit on us as soon as those coils got wet. Well, we made it to the barn, threw open the gate, drove the car into the barn lot. As we closed the fence gate, we saw that the barn doors were open and standing in the barn doors was a vicious looking big Missouri stud mule stomping his feet and rearing and kicking and chomping his teeth. He wasn’t going to give up that barn for no rain storm!

Somehow we managed to trick him, or by a flurry of rocks, got him out of the barn into the rainy pasture and drove the old Ford truck in. We closed the barn doors and Mrs. Horne and mother commenced ringing out the water while dad and us kids were more concerned with the mad stud mule. He kept on his mean antics of running and rearing up to the barn door and his hooves made an awful clatter against the doors, and he would bite at the door. Then dropping down on all four feet, he would whirl, lashing or kicking out with his hind feet, giving a broadside with both hind feet at once. We found ourselves in a very bad spot.

We tore out the mangers and putting the poles up against the barn doors, we backed the truck back-end up to hold the poles in place. We were a little safer. This beating went on all night. We crawled under the car for safety. It helped a little, but no one slept as the barn began to leak; the water was puddling, and it kept on raining. In the morning, we broke out some dry bread and those wonderful old standbys, Van Camps, pork and beans with the orange juice sucked out of those same oranges the old Lady Horn was making us save for the dry desert. We had already crossed the desert!

And that damn mule was still out for blood, and dad began to regret having started a fuss with him. For it was plain to see, he wasn’t going to let us get away. I have since that time read in the Outdoor and Safari magazines articles expounding on the lions, rhinos, water Buffalo, wild bears and wild boars all kinds of stories about world’s most vicious enemies. But I’ll lay you all I own on a wild stallion or a big stud mule, because more after when they came upon you with malicious intent, you find yourself more in their made-to-order, circumstance or element.

Well, about 8:00 or 9:00 a farmer came by the beleaguered barn in a wagon drawn by two big black workhorses, at least bigger than that mule. He was a big one, of course, in those days a neighbor was a beloved member of Adam’s race, and perceiving our predicament, he offered to help. He grabbed a big one-inch rope on the wagon bed, and dad and the farmer took the big black team unhitched from the wagon.

Dad threw the rope around that mule’s neck and flipped a 1/2 hitch over his nose and took his dally around the harness frame, while in Spanish fashion the farmer reached down and with a flip of the wrist picked up the mule’s hind feet and then in an angry manner, they belayed and jerked that mule off his feet, then dad unhooked a tug that was hooked up in the proper place and took a double half hitch around that tug, he hauled that mule on the wet grass by the muzzle right out the gate, and dad and the good neighbor left the mule tied down in the road.

The man then said it was his mule and offered to pay any damages. Dad declined the offer. The man said he would go on to the ranch and come back with a ranch hand and loosen the mule and let him up. Said if he stayed tied down all day, he would get tolerable, as he had to do that often to take the meanness out of him and make him tolerable. Said he was going to shoot him as soon as he bred some mares.

So, after drying the coils in the ignition system, we went on our way to Camas Prairie. Dad said, “You learned a lesson today. Never forget it. It may be impossible to find good neighbors like that in your day.”

We stopped in some little town and Dad mentioned there was some Hot Springs in that long building over there. Immediately I ran over to see where the Hot Springs was. Well, they drove off and left me! When I came out, they were gone. I was lost. I began to bawl and cry something awful and run around, and it wasn’t long till I was really lost. About three miles on their way, those two enemies of mine, Mrs. Horn and Mildred, told dad and mother I wasn’t there with them. They finally found out where they lost me and after a search of the town they found me. We reached Fairfield and as some of the relatives lived nearby, we spent a few days visiting there.

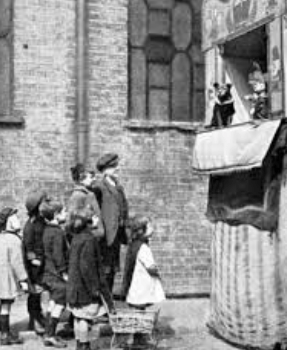

We went to a circus or a carnival. I remember a man that would swallow needles and thread and string up in his belly. He pulled the thread and needles, all strung up, from his mouth. And we saw our first and only Punch and Judy show. We first met some of our cousins and their aunts and uncles, dad’s family, and had a good visit and the red fish mother had packed astonished the relatives. We left the Camas Prairie after seeing Grandma Hicks for the first and only time and dropped down on the Snake River near King Hill. We crossed the Snake River on that bridge near there and went up to that ranch on the other side of the river to get a truckload of watermelons where we had another adventure.

We crossed the old narrow bridge in low gear, half afraid that it might not hold the old Model T. I see the bridge is still standing over the Snake River near King Hill. It is more than 50 years ago. It was an old bridge then.

Driving along a grade up-river about 1/4 mile, we soon came to the ranch. Piling out of the truck, we commenced to get acquainted, and we greeted old friends, and was met on the same principle as the Indians would greet their friends. “It is very good, my brother, that you have come so far to see us,” was the attitude that seemed to prevail. Every person you would meet in those days was a friend with no reservations until you made him an enemy. With no suspicion, they seem to recognize that there is a man in whom there is no guile, as Christ said of Nathaniel. There was a table out under the trees that spattered all the yard, making plenty of shade and plenty of grass. The man said, “Come join us. We were about to have a strawberry and cream feast, and we just needed someone to help us eat them. The berries grow stale and rotten and the cream sours if not eaten when ready.”

My mother, bless her, knew all about the loneliness of a farm wife and the longing to have someone to visit with. It pleased us all very much when she said we would all like that very much, and you must let me be of some help. And as the saying goes, I’ll speak for my supper, because I can’t sing. And while the bowls of berries and #3 buckets of rich cream, and the bowls and spoons was getting put on the table, out on the lawn us horde of children were getting our places on the benches that were there for us to set on.

My mother, true to her word, began to recite poetry, which was very popular in those days. And particularly in high school, I knew her to be the most recitive person that I have ever seen and heard. And she went through a select 10 or 15 of her shortest poems.

One night on a challenge from Dad we were to hear her speak Evangeline by young Longfellow. It took her from 4:00 to after 2:00 in the morning, and I never realized the potential, the pitch, intentionality of such a mind and memory until the time she was gone. And while a young man, I have seen so many miracles of her memory.

Her recitals seemed to astonish those folks very much and pleased the children immensely. One more attribute to her, she grieved whenever she tried to speak Hiawatha because she could only get halfway through it. As she said, she told me how to do it. “You just make up a tune that fits the poem, and about two or three times you sing the song, it’s all learned. Then you just convert it back into a poem. It’s easy!”

I have tried it over the years and found it works. People would hear me singing a poem and would often say that’s a poem, not a song. I would say I know it’s a poem; I’m just learning it. They would say, “Crazy, crazy man!”

While the men were talking dad said, “I’ve been living up at Little Missouri and them farmers up that way can’t raise those good old red long watermelons. In fact, they haven’t seen a big, red melon since they left Missouri. I was raised down in the Boise Valley, and I know these melons that are grown in this sandy soil along the Snake River.” And he went on, “I was thinking about throwing a little hay in the truck and then lying about 24 big melons in to take back to Little Missouri with me just to show them off.”

“Good idea, said the farmer. Have a little fun with those boys and, well, I got about two or three hundred down in the orchard that I raised for the hogs. Hey, you kids, take that boy and girl, (meaning my sister and I) with you speaking to a boy and girl about her size and you down in the orchard and kick a few melons, and see if we can get about 24 that ain’t too ripe. The ripe ones won’t stand the trip, even in hay. The hogs need some to eat anyway.”

The boy and girl immediately led us down into the orchard melon patch and began testing the melons by kicking them with their feet. The boy, saying that I was astonished by his wastefulness, explained, “The ruthless reason to me, you see, a hog can’t bust a melon with his nose, and he ain’t got sense enough to use his feet. So, the ones that bust open are too ripe to haul in your dad’s truck. And when they bust open, the hogs can eat them. The ones that are just a little greener and don’t burst open when I kick them and are nice pretty melons, they’re the ones we pick off the vine and carry up to the lawn for you folks to buy and haul away and might stand the trip for two or three days before they also ripen up and bust. The only fault with the mess is that when we start busting melons, we got to watch for a mean boar hog and the swarms of yellow jackets.”

“I’m not afraid of those yellow jackets,” and I bragged proudly how they will never sting me. “I’m used to bees. We keep a bee farm,” I bragged proudly. “As I said, all type of bees are my friends. My mother can talk to the bees.” And I know he believed that, especially after he had heard her recitation at the strawberry feast.

We stayed the night as we had our beds and blankets in the truck and were prepared for just such an occasion. We arose early with some help with that delicious cream and milk. We feasted on the most delicious hot cakes, Mother’s oats and cereal and real ranch butter. We all feasted on the same table out under the shade of those beautiful trees. Then all us kids packed up the watermelons that was selected as the best for the trip. The boy embarrassed me by saying, “Look daddy, he’s eating some watermelon.” I immediately stopped when the family began to laugh at me.

Dad and the nice man got some hay in the truck. Mama carefully packed the melons in the hay. The man warned dad, “You want to watch out. Some of them melons may ferment inside when they get mushy and warm and make them Missourians drunk.”

Then began the argument over money. The man would not take any money and persisted. We had done him a favor by taking the strawberries and cream and melons off his hands. Dad was just as stubborn for taking something for no pay. Mother and the farm lady finally settled the argument by giving the boy and girl one quarter each. I remember how proud they were. That was the first money they ever earned. And try as we could, we could not pay more. What we learned in the memories was worth so much more than that.

So, we headed up to the Snake River, over by Arco and toward Mackie, over the Double Springs Pass on the head of the Bessemer Road, through the Grove of trees in the valley of the Green Trees, and on down to our old homestead on Dry Gulch (Pahsimeroi, Idaho), nursing and tending those watermelons along with swarms of yellow jackets swarming to the sweet nectar. And every once in a while, they would pop, pop. We were tired of the fermenting smell and would have gladly got rid of them, but Dad was determined for some reason to show them off.

Leave a comment